The link between dissociation and psychological trauma: how psychedelics can restore a basic sense of security

-

17 November 2025Переглянуто: 598

Introduction

The study of dissociative states and related disorders is relevant due to their significant impact on treatment outcomes and disease progression. Such states are often not only persistent but also initially inconspicuous in clinical diagnosis, which limits the possibilities for timely intervention, negatively affecting psychological well-being and the level of adaptation. (Lebois et al., 2022; Lyssenko et al., 2018). At the same time, dissociative symptoms are relatively common and are not limited to classic dissociative disorders. They can be observed in post-traumatic, personality, and affective disorders, as well as in everyday life—for example, in cases of fatigue.

One of the challenges for the healthcare system is to understand the factors that underlie these disorders, assess their actual impact on life and health, and consider new theoretical approaches and promising treatment methods. Research into dissociative states can provide information not only for clinical practice but also for neurobiology, offering a deeper understanding of the complex interactions between brain function, consciousness, and psychopathology. Promising areas of contemporary therapy that have regained relevance in scientific and clinical discourse include approaches based on the use of psychoactive substances that can deepen our understanding of the neurobiological mechanisms of dissociation.

Trauma and dissociation

Trauma has a significant impact on a person's psyche—if such an experience is lived through in childhood, it can increase the likelihood of developing mental disorders later in life, and in adulthood, it can change patterns of thinking and behavior, complicating the formation of close relationships and contributing to a decline in trust. But why does trauma have such an impact?

Psychological trauma is a phenomenon that arises as a result of "excessive" physical and emotional impact, which includes a personally significant event or information (violence, torture, natural disasters, emotional abuse, etc.) and is experienced as a severe shock and catastrophe (Neuner, 2023). Such impact always exceeds the psyche's ability to cope and adapt at the moment. It is typically accompanied by an intense feeling of helplessness, loss of control, and threat (to life, physical integrity, important relationships, or values) (Vignato et al., 2017; Weis et al., 2022).

Childhood trauma is a traumatic experience that occurs at an age when emotional regulation, a sense of basic security, and healthy attachment are still being established. The less mature the nervous system is, the greater the dependence on important adults. During childhood, traumatic experiences are more easily engraved and reinforced. This is due to structural and functional changes in the amygdala and hippocampus, which are actively involved in processing and regulating emotional responses.(Dannlowski et al., 2012; Hanson et al., 2015). The reduction in the volume of these areas, caused by the cumulative effect of stressors, is associated with an increased risk of emotional problems in the future. This occurs, among other things, due to the formation of persistent negative patterns—perceptions of the world, oneself, and others—which are the basis for persistent stress reactions and difficulties in emotional regulation in the future.(Pagliaccio et al., 2015).

The phenomenon of a kind of "disconnection" from excessive emotions during and after trauma is called dissociation. It is a mechanism that protects the psyche from excessive stress—stress that exceeds our internal resources. At first, dissociation may occur as an instantaneous protective reaction of the psyche, but over time it can become entrenched, turning into a permanent way of avoiding emotional experiences and reducing mental pain.

If dissociation becomes chronic, it can undermine the basic sense of security — a deep conviction that the world is predictable and that you and your loved ones are safe. This feeling is formed in early childhood, when a child does not encounter cruelty or neglect. If they grow up in conditions of constant threat, basic anxiety, distrust of the world, and attachment disorders arise.(Bell et al., 2019). In such cases, dissociation becomes a kind of defense mechanism—a way for the psyche to distance itself from an unbearable experience in order to maintain functioning and the ability to adapt. (Lebois et al., 2020). The link between a breach of basic trust in the world and trauma also explains why traumatic experiences associated with the actions of others—such as violence or torture—are more pronounced than those associated with natural factors, such as natural disasters. (Bell et al., 2019). If the world is perceived as hostile and unpredictable, then a person may unconsciously choose to distance themselves from it. Often, children who have experienced violence learn to imagine that it is not happening to them, or that they are "somewhere else". (Vonderlin et al., 2018; Choi et al., 2017). Essentially, thoughts, emotions, memories, and the body become disconnected for the purpose of self-defense.

When trauma occurs in adulthood, it disrupts our belief system about the safety and meaningfulness of the world and destroys our sense of security. The constant lack of security, in turn, reinforces the tendency toward dissociation. (Lebois et al., 2020). This is also associated with difficulties in establishing and maintaining close relationships, decreased trust in others, and a loss of control over one's own life.

Consequences of dissociation

Dissociative states are actually relatively common, although they have long been underestimated in clinical practice. People may experience them without even realizing it, while healthcare professionals often overlook such states. (Lebois et al., 2022; Lyssenko et al., 2018). This happens because in mild forms, dissociation may manifest itself in subtle ways—such as habitual distraction, forgetfulness, difficulty in building relationships, etc.(McWhirter et al., 2022; Krause-Utz et al., 2017). It can often be detected through the examination of related symptoms—anxiety, depression, self-harm, or substance abuse. Dissociation and related symptoms reinforce each other, creating a vicious cycle. Therefore, by distancing themselves from negative experiences, people also distance themselves from positive emotional experiences, which reinforces their depressive view of the world. This leads to feelings of alienation and difficulty experiencing love, joy, and pleasure.

Another major consequence is an impaired ability to distinguish between safe and dangerous situations, which occurs due to a violation of basic security and attachment. For example, a person who has experienced childhood abuse by loved ones may not recognize "red flags" in adulthood, which can lead to re-traumatization (e.g., through abusive relationships).

The neurobiology of dissociation

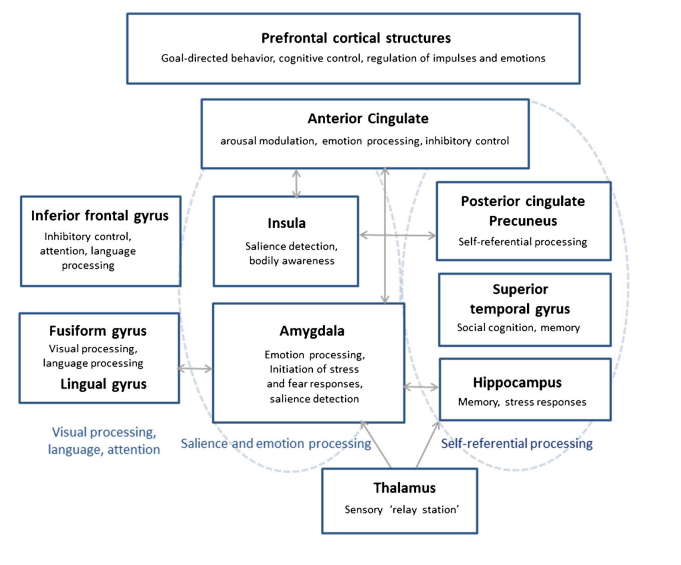

Schematic representation of the neurobiological basis of dissociative processes (Krause-Utz et al., 2017).

From a neurobiological point of view, dissociative processes are the coordinated interaction of separate brain systems. Depending on the characteristics of their complex interaction, different manifestations and intensities of dissociation are observed. To understand these characteristics, it is worth considering the role of the main structures separately.

The prefrontal cortex can be called key in the genesis of dissociative processes. During traumatic experiences, it becomes hyperactive, taking on a controlling role—helping to suppress other brain structures, such as the hippocampus (involved in memory processes) and limbic structures (involved in emotional responses, "fight-flight-freeze"). In fact, the prefrontal cortex "unlocks" the emotional component of our brain, allowing us to remain detached and insensitive to painful experiences. This explains the phenomenon of "emotional numbness" — the feeling that "this is not happening to me."

The cognitive control of the prefrontal cortex over memory is also responsible for suppressing memories and, consequently, the inability to integrate them into our biography, inhibiting the spread of neural excitation in areas of the hippocampus. Under normal circumstances, the hippocampus integrates an event into a coherent memory episode, linking the sequence of events, individual details, and emotional attitudes toward them. Traumatic memories are often stored in fragments, without proper connection to time and context, creating memories in the form of isolated images and impressions that are stored as if in isolation. This can also be explained by the effect of excess cortisol (a stress-related hormone) on our psyche, the understanding of which is particularly useful in explaining clinical cases of psychogenic amnesia.(Lupien et al., 1998). Integrating fragmented memories into the overall narrative of our lives is the basis of therapeutic action, which reduces the need for pathological prefrontal inhibition.

The amygdala, as a key structure of the limbic system, helps process emotions, particularly anxiety and fear, and form emotional memories. If the connection between the amygdala and the hippocampus is disrupted, this also contributes to the creation of fragmented emotional memories (for example, a person may remember feelings of panic but have difficulty recalling other aspects). Conversely, if the limbic system is insufficiently inhibited, a strong affective response occurs in response to a trauma-related stimulus, such as intense fear, flashbacks, panic attacks, etc.

The insula (island lobe) is one of the components of the cerebral cortex associated with physical experiences of emotional states and connection with the body. It helps to capture and interpret signals from internal organs and their external manifestations (stiffness, rapid heartbeat, shortness of breath, etc.). The insula is also subject to inhibitory signals from the prefrontal cortex, which manifests itself in difficulties in recognizing physical markers of tension – for example, muscle tension, which can be noticed at the stage when the muscles begin to "twitch" from overload. Contact with the body is important because it allows us to notice our condition, relax, and stabilize. When we do not notice these signals, it can increase the level of tension—for example, shallow breathing leads to a decrease in the level of carbon dioxide in the blood, causing tachycardia, dizziness, and similar symptoms that can be interpreted as increased anxiety.(Zvolensky & Eifert, 2001; Paulus, 2013). At the same time, when we have less connection with our sensory perceptions, it becomes easier for us to "disconnect" from the world. In extreme cases, the body may cease to feel like an integral part of us—then we can talk about depersonalization.

In cases where such states of detachment are not permanent but arise in response to a specific trigger, the basal ganglia—structures with complex multifunctional connections—take the lead. They participate in the integration and modulation of information from other areas of the brain, as well as in emotional and cognitive control, attention regulation, and memory. According to some assumptions, it may be a kind of "switch" between different dissociative states and, conversely, the usual state of presence. (Roydeva & Reinders, 2021). In various psychotherapeutic methods, this corresponds to the concepts of "personality fragments (modes)," "subpersonalities," and others.

Psychoactive substances in therapy

Changing current drug policy — moving from criminalization to regulated therapeutic decriminalization of psychedelics — has contributed to growing interest in treatment methods that use psychoactive substances — in particular, psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy and psychedelic integration. The applicability of these methods seems interesting because dissociative disorders are more complex and difficult to treat, as they can interfere with emotional learning and engagement in treatment. (Lanius et al., 2018; Krause-Utz et al., 2021). In classical psychotherapy methods, dissociation can manifest itself as detachment from sensitive topics, a feeling of "emptiness in the head" or "not knowing what to say." This is a normal feature of the therapy process, but it slows down its progress. In more unfortunate scenarios, the psychotherapist's patient may simply be unaware of their psychological problems, which will manifest themselves in external difficulties in other areas of life — for example, conflicts with loved ones, constant exhaustion, etc. Signals from the body about fatigue or tension are also difficult to notice due to a disturbed sense of physicality—difficulty in feeling one's body as a safe space, a way out of a state of chronic tension.

(Morrison, 2016; Černis et al., 2021). Dissociation occurs automatically when something reminds us of trauma, so it is difficult to stop it by simple willpower. Rebuilding the patterns by which our brain responds requires a lot of effort.

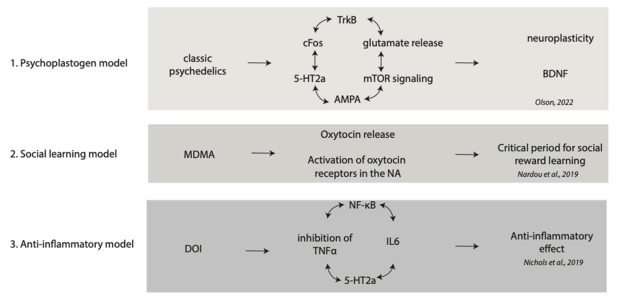

The effects of psychoactive substances contribute to increased neuroplasticity—the ability to reorganize and form new neural connections, opening a "window of flexibility" for a person to fully assess and integrate trauma, adjusting their internal perceptions of it, themselves, and the world. (Knudsen, 2023; Calder & Hasler, 2023). In other words, such intervention aims to address the root cause of the disorder, rather than just its symptoms. The mechanism for increasing neuroplasticity is the effect of classic psychedelics (psilocybin, LSD) on serotonin receptors in the brain, which promotes the release of the neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which in turn stimulates the growth of dendrites and the formation of new synapses, including in those areas of the brain involved in the processes of traumatic dissociation (hippocampus, prefrontal cortex)(Savalia, Shao, & Kwan, 2021; Kwan et al., 2022).

Changes in neuroplasticity through the influence on the serotonergic system also affect the modulation of memory processes, stress responses, and emotional processing, which can neurobiologically reduce the intensity of emotional and traumatic experiences. (Raut et al., 2022). Softening emotional reactions allows one to return to traumatic memories and process them without excessive distress. Calming emotional pain and increasing brain plasticity create conditions for temporarily "muting" the psyche's automatic defensive reactions. This allows the neural networks responsible for self-observation, reflection, and integration of experience to rethink and integrate the traumatic event and move on. In psychedelic-assisted therapy, this process often leads to the phenomenon of "insight." (Breeksema et al., 2020).

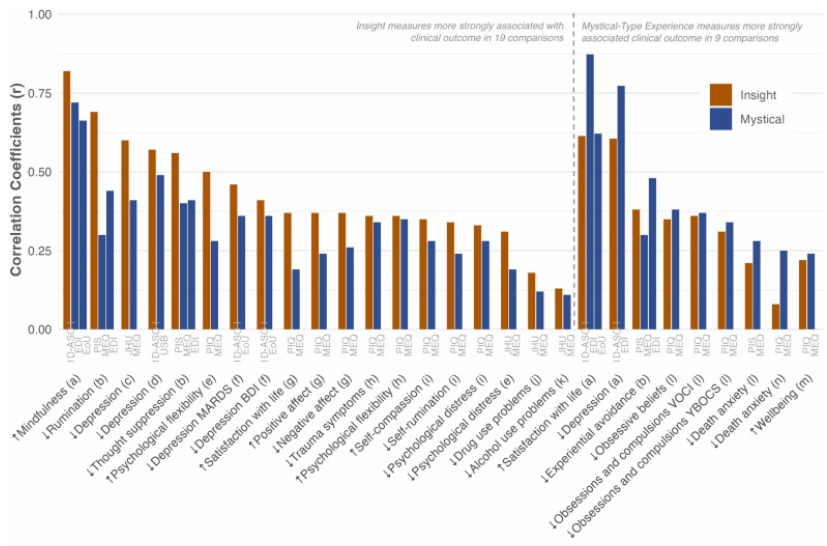

The phenomenon of insight in psychedelic-assisted therapy refers to a sudden, profound change in understanding or perspective of oneself, others, or the world that feels true or reliable. (Kugel et al., 2025). In the context of trauma work, insight takes on therapeutic significance because it allows a person to fully realize or experience the event that caused the trauma—to integrate the new experience into the narrative of their life. Thus, dissociation ceases to be necessary as a means of pathological defense against painful experiences. This explains why "insight" has a greater impact on clinical symptoms than the mystical experiences themselves, which have traditionally received more attention in research.(Breeksema et al., 2020; Williams et al., 2021).

Comparing the relationship and impact of insights and mystical experiences on clinical indicators (Kugel et al., 2025).

When using MDMA in therapy, its prosocial empathogenic effects come to the fore – increased trust, attachment, and self-compassion. (Wolfgang et al., 2024). Social isolation and feelings of loneliness are factors that often go hand in hand with dissociation and contribute to its progression. (Xiong et al., 2022). Given that injuries caused by the actions of others have a particularly profound emotional impact, it can be assumed that the empathogenic properties of MDMA allow patients to be more open to positive social experiences. This creates a basis for reducing feelings of alienation, forming new models of trust, and further positive changes in the interpersonal sphere. (Taylor et al., 2024). In a therapeutic alliance, this can contribute to its deepening by strengthening the sense of security and trust in the therapist, helping to consolidate the long-term positive effects of therapy and avoiding "resistance" in the work.

This works thanks to the social learning and reward effect—a process by which people become more sensitive to positive social cues and interactions. Some psychedelics can open up a "critical period" for social learning, mediated by the release of serotonin and oxytocin. (van Elk & Yaden, 2022). This opens up opportunities to revisit the path of social learning — a process in which patients can rethink and reconsolidate previously formed maladaptive patterns — stable cognitive structures that shape a person's perception of themselves, others, and the world in general. For example, personality disorders are often characterized by basic negative beliefs such as "others cannot be trusted," "they want to harm me," "I am worthless." Such beliefs are reinforced by previous traumatic experiences, contributing to the development of dissociative mechanisms as a means of psychological defense.

Over time, such mechanisms become chronic, maintaining emotional detachment, reduced empathy, and impaired interpersonal trust—phenomena that are often observed, for example, in borderline personality disorder. (Brown & Reuber, 2016; Weisz & Cikara, 2021). The empathogenic and prosocial properties of MDMA create conditions for "rewriting" these patterns in a safe therapeutic space—the flexibility of social perception of positive signals promotes the integration of new, more adaptive ideas about oneself and the world.

Various theoretical models of the therapeutic effects of psychoactive substances (van Elk & Yaden, 2022).

Noteworthy is the effect on dissociative states through the provocation of drug-induced dissociation. This is explained by various neurobiological mechanisms involved in the action of ketamine—NMDA receptor antagonism (glutamatergic system)—and in trauma—disruption of brain neural network integration. (Moran et al., 2015; Bottemanne et al., 2023). Ketamine dissociation is a pharmacologically induced state that also involves changes in the serotonergic, endocannabinoid, and opioid systems, accompanied by a decrease in prefrontal cortex activity and a simultaneous increase in the interaction of limbic structures and the neural network of the brain responsible for the integration of experience, self-reflection, and autobiographical memories(Lanius et al., 2018). Thanks to this action, ketamine dissociation can create an effect of detachment from the external environment while maintaining contact with internal experiences, allowing the patient to observe and reconsolidate traumatic memories without excessive emotional overload.

That is, unlike defensive dissociation, which is a mechanism for avoiding unbearable affect, and pathological dissociation, which is characterized by chronic fragmentation of the personality structure and impaired integration of consciousness, the medication form is controlled and therapeutic in nature. (Lyssenko et al., 2018). It is not a manifestation of the disintegration of neural networks and structures, but rather a temporary state of neuroplasticity that opens up the possibility of adaptive trauma processing and the gradual integration of previously fragmented experiences.

Conclusion

The use of psychoactive substances for therapeutic purposes may be a promising direction in the treatment of complex conditions accompanied by dissociation and having a complex symptomatic profile. The potential of such interventions lies in their ability to reduce emotional pain, increase adherence to therapy, and temporarily enhance brain neuroplasticity. It is thanks to these changes that patients are able to rethink their experiences, learn new patterns of thinking and behavior, and integrate more adaptive ways of responding.

However, this increased mental plasticity is temporary and creates a window of heightened vulnerability. During this period, it is particularly important what happens to the patient, what changes in perception they assimilate—whether adaptive or destructive for themselves. (Penn et al., 2021; Palitsky et al., 2023). Therefore, an important factor in the safety and effectiveness of interventions using psychoactive substances is the presence of a qualified specialist who can provide adequate guidance and support for the process of integrating changes. The therapeutic use of psychoactive substances should be carried out exclusively within the framework of medical programs according to specific clinical protocols, taking into account legal, ethical, and medical aspects, careful screening for contraindications, and monitoring of the patient's condition.

Despite its significant therapeutic potential, the status of this approach remains uncertain. The use of psychoactive substances requires further clinical research to study their long-term effects, precise neurobiological mechanisms of action, and optimal protocols for different types of dissociative disorders and conditions involving dissociative symptoms. And although the risks remain significant, for some patients with severe, treatment-resistant conditions, such methods may be the "last hope" for recovery and adaptation.

References

-

Abdallah, C. G., De Feyter, H. M., Averill, L. A., Jiang, L., Averill, C. L., Chowdhury, G. M. I., Purohit, P., de Graaf, R. A., Esterlis, I., Juchem, C., Pittman, B. P., Krystal, J. H., Rothman, D. L., Sanacora, G., & Mason, G. F. (2018). The effects of ketamine on prefrontal glutamate neurotransmission in healthy and depressed subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology, 43(10), 2154–2160.

-

Bell, V., Robinson, B., Katona, C., Fett, A.-K., & Shergill, S. (2019). When trust is lost: The impact of interpersonal trauma on social interactions. Psychological Medicine, 49(6), 1041–1046.

-

Bottemanne, H., Berkovitch, L., Gauld, C., Balcerac, A., Schmidt, L., Mouchabac, S., & Fossati, P. (2023). Storm on predictive brain: A neurocomputational account of ketamine antidepressant effect. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 154, 105410.

-

Breeksema, J. J., Niemeijer, A. R., Krediet, E., Vermetten, E., & Schoevers, R. A. (2020). Psychedelic Treatments for Psychiatric Disorders: A Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis of Patient Experiences in Qualitative Studies. CNS Drugs, 34(9), 925–946.

-

Brown, R. J., & Reuber, M. (2016). Psychological and psychiatric aspects of psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES): A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 45, 157–182.

-

Calder, A. E., & Hasler, G. (2023). Towards an understanding of psychedelic-induced neuroplasticity. Neuropsychopharmacology: Official Publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 48(1), 104–112.

-

Černis, E., Beierl, E., Molodynski, A., Ehlers, A., & Freeman, D. (2021). A new perspective and assessment measure for common dissociative experiences: «Felt Sense of Anomaly». PloS One, 16(2), e0247037.

-

Choi, K. R., Seng, J. S., Briggs, E. C., Munro-Kramer, M. L., Graham-Bermann, S. A., Lee, R. C., & Ford, J. D. (2017). The Dissociative Subtype of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Among Adolescents: Co-Occurring PTSD, Depersonalization/Derealization, and Other Dissociation Symptoms. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 56(12), 1062–1072.

-

Dannlowski, U., Stuhrmann, A., Beutelmann, V., Zwanzger, P., Lenzen, T., Grotegerd, D., Domschke, K., Hohoff, C., Ohrmann, P., Bauer, J., Lindner, C., Postert, C., Konrad, C., Arolt, V., Heindel, W., Suslow, T., & Kugel, H. (2012). Limbic scars: Long-term consequences of childhood maltreatment revealed by functional and structural magnetic resonance imaging. Biological Psychiatry, 71(4), 286–293.

-

Hanson, J. L., Nacewicz, B. M., Sutterer, M. J., Cayo, A. A., Schaefer, S. M., Rudolph, K. D., Shirtcliff, E. A., Pollak, S. D., & Davidson, R. J. (2015). Behavioral problems after early life stress: Contributions of the hippocampus and amygdala. Biological Psychiatry, 77(4), 314–323.

-

Knudsen, G. M. (2023). Sustained effects of single doses of classical psychedelics in humans. Neuropsychopharmacology: Official Publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 48(1), 145–150.

-

Krause-Utz, A., Frost, R., Chatzaki, E., Winter, D., Schmahl, C., & Elzinga, B. M. (2021). Dissociation in Borderline Personality Disorder: Recent Experimental, Neurobiological Studies, and Implications for Future Research and Treatment. Current Psychiatry Reports, 23(6), 37.

-

Krause-Utz, A., Frost, R., Winter, D., & Elzinga, B. M. (2017). Dissociation and Alterations in Brain Function and Structure: Implications for Borderline Personality Disorder. Current Psychiatry Reports, 19(1), 6.

-

Kugel, J., Laukkonen, R. E., Yaden, D. B., Yücel, M., & Liknaitzky, P. (2025). Insights on psychedelics: A systematic review of therapeutic effects. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 173, 106117.

-

Kwan, A. C., Olson, D. E., Preller, K. H., & Roth, B. L. (2022). The neural basis of psychedelic action. Nature Neuroscience, 25(11), 1407–1419.

-

Lanius, R. A., Boyd, J. E., McKinnon, M. C., Nicholson, A. A., Frewen, P., Vermetten, E., Jetly, R., & Spiegel, D. (2018a). A Review of the Neurobiological Basis of Trauma-Related Dissociation and Its Relation to Cannabinoid- and Opioid-Mediated Stress Response: A Transdiagnostic, Translational Approach. Current Psychiatry Reports, 20(12), 118.

-

Lanius, R. A., Boyd, J. E., McKinnon, M. C., Nicholson, A. A., Frewen, P., Vermetten, E., Jetly, R., & Spiegel, D. (2018b). A Review of the Neurobiological Basis of Trauma-Related Dissociation and Its Relation to Cannabinoid- and Opioid-Mediated Stress Response: A Transdiagnostic, Translational Approach. Current Psychiatry Reports, 20(12), 118.

-

Lebois, L. A. M., Kumar, P., Palermo, C. A., Lambros, A. M., O’Connor, L., Wolff, J. D., Baker, J. T., Gruber, S. A., Lewis-Schroeder, N., Ressler, K. J., Robinson, M. A., Winternitz, S., Nickerson, L. D., & Kaufman, M. L. (2022). Deconstructing dissociation: A triple network model of trauma-related dissociation and its subtypes. Neuropsychopharmacology, 47(13), 2261–2270.

-

Lebois, L. A. M., Li, M., Baker, J. T., Wolff, J. D., Wang, D., Lambros, A. M., Grinspoon, E., Winternitz, S., Ren, J., Gönenç, A., Gruber, S. A., Ressler, K. J., Liu, H., & Kaufman, M. L. (2021). Large-Scale Functional Brain Network Architecture Changes Associated With Trauma-Related Dissociation. American Journal of Psychiatry, 178(2), 165–173.

-

Lupien, S. J., de Leon, M., de Santi, S., Convit, A., Tarshish, C., Nair, N. P. V., Thakur, M., McEwen, B. S., Hauger, R. L., & Meaney, M. J. (1998). Cortisol levels during human aging predict hippocampal atrophy and memory deficits. Nature Neuroscience, 1(1), 69–73.

-

Lyssenko, L., Schmahl, C., Bockhacker, L., Vonderlin, R., Bohus, M., & Kleindienst, N. (2018). Dissociation in Psychiatric Disorders: A Meta-Analysis of Studies Using the Dissociative Experiences Scale. American Journal of Psychiatry, 175(1), 37–46.

-

McWhirter, L., Smyth, H., Hoeritzauer, I., Couturier, A., Stone, J., & Carson, A. J. (2023). What is brain fog? Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 94(4), 321–325.

-

Moran, R. J., Jones, M. W., Blockeel, A. J., Adams, R. A., Stephan, K. E., & Friston, K. J. (2015). Losing Control Under Ketamine: Suppressed Cortico-Hippocampal Drive Following Acute Ketamine in Rats. Neuropsychopharmacology, 40(2), 268–277.

-

Morrison, I. (2016). ALE meta-analysis reveals dissociable networks for affective and discriminative aspects of touch. Human Brain Mapping, 37(4), 1308–1320.

-

Neuner, F. (2023). Physical and social trauma: Towards an integrative transdiagnostic perspective on psychological trauma that involves threats to status and belonging. Clinical Psychology Review, 99, 102219.

-

Pagliaccio, D., Luby, J. L., Bogdan, R., Agrawal, A., Gaffrey, M. S., Belden, A. C., Botteron, K. N., Harms, M. P., & Barch, D. M. (2015). Amygdala functional connectivity, HPA axis genetic variation, and life stress in children and relations to anxiety and emotion regulation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 124(4), 817–833.

-

Palitsky, R., Kaplan, D. M., Peacock, C., Zarrabi, A. J., Maples-Keller, J. L., Grant, G. H., Dunlop, B. W., & Raison, C. L. (2023). Importance of Integrating Spiritual, Existential, Religious, and Theological Components in Psychedelic-Assisted Therapies. JAMA Psychiatry, 80(7), 743–749.

-

Paulus, M. P. (2013). The breathing conundrum – interoceptive sensitivity and anxiety. Depression and anxiety, 30(4), 315–320.

-

Penn, A., Dorsen, C. G., Hope, S., & Rosa, W. E. (2021). CE: Psychedelic-Assisted Therapy. AJN The American Journal of Nursing, 121(6), 34.

-

Raut, S. B., Marathe, P. A., van Eijk, L., Eri, R., Ravindran, M., Benedek, D. M., Ursano, R. J., Canales, J. J., & Johnson, L. R. (2022). Diverse therapeutic developments for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) indicate common mechanisms of memory modulation. Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 239, 108195.

-

Roydeva, M. I., & Reinders, A. A. T. S. (2021). Biomarkers of Pathological Dissociation: A Systematic Review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 123, 120–202.

-

Savalia, N. K., Shao, L.-X., & Kwan, A. C. (2021). A Dendrite-Focused Framework for Understanding the Actions of Ketamine and Psychedelics. Trends in Neurosciences, 44(4), 260–275.

-

Taylor, C. T., Stein, M. B., Simmons, A. N., He, F., Oveis, C., Shakya, H. B., Sieber, W. J., Fowler, J. H., & Jain, S. (2024). Amplification of Positivity Treatment for Anxiety and Depression: A Randomized Experimental Therapeutics Trial Targeting Social Reward Sensitivity to Enhance Social Connectedness. Biological Psychiatry, 95(5), 434–443.

-

Tian, F., Lewis, L. D., Zhou, D. W., Balanza, G. A., Paulk, A. C., Zelmann, R., Peled, N., Soper, D., Santa Cruz Mercado, L. A., Peterfreund, R. A., Aglio, L. S., Eskandar, E. N., Cosgrove, G. R., Williams, Z. M., Richardson, R. M., Brown, E. N., Akeju, O., Cash, S. S., & Purdon, P. L. (2023). Characterizing brain dynamics during ketamine-induced dissociation and subsequent interactions with propofol using human intracranial neurophysiology. Nature Communications, 14(1), 1748.

-

van Elk, M., & Yaden, D. B. (2022). Pharmacological, neural, and psychological mechanisms underlying psychedelics: A critical review. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 140, 104793.

-

Vignato, J., Georges, J. M., Bush, R. A., & Connelly, C. D. (2017). Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PPTSD) in the Perinatal Period: A Concept Analysis. Journal of clinical nursing, 26(23–24), 3859–3868.

-

Vonderlin, R., Kleindienst, N., Alpers, G. W., Bohus, M., Lyssenko, L., & Schmahl, C. (2018). Dissociation in victims of childhood abuse or neglect: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Medicine, 48(15), 2467–2476.

-

Weis, C. N., Webb, E. K., deRoon-Cassini, T. A., & Larson, C. L. (2022). Emotion Dysregulation Following Trauma: Shared Neurocircuitry of Traumatic Brain Injury and Trauma-Related Psychiatric Disorders. Biological Psychiatry, 91(5), 470–477.

-

Weisz, E., & Cikara, M. (2021). Strategic Regulation of Empathy. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 25(3), 213–227.

-

Williams, M. T., Davis, A. K., Xin, Y., Sepeda, N. D., Grigas, P. C., Sinnott, S., & Haeny, A. M. (2021). People of color in North America report improvements in racial trauma and mental health symptoms following psychedelic experiences. Drugs (Abingdon, England), 28(3), 215–226.

-

Wolfgang, A. S., Fonzo, G. A., Gray, J. C., Krystal, J. H., Grzenda, A., Widge, A. S., Kraguljac, N. V., McDonald, W. M., Rodriguez, C. I., & Nemeroff, C. B. (2025). MDMA and MDMA-Assisted Therapy. American Journal of Psychiatry, 182(1), 79–103.

-

Xiong, Y., Hong, H., Liu, C., & Zhang, Y. Q. (2023). Social isolation and the brain: Effects and mechanisms. Molecular Psychiatry, 28(1), 191–201.

-

Zvolensky, M. J., & Eifert, G. H. (2001). A review of psychological factors/processes affecting anxious responding during voluntary hyperventilation and inhalations of carbon dioxide-enriched air. Clinical Psychology Review, 21(3), 375–400.