Invisible Wounds. The mental health crisis in Ukraine through the eyes of local experts

-

23 September 2025Переглянуто: 7724

„Mental health must be a priority for our nation to overcome this crisis, survive and prevail.“

Foreword

In April 2023, I participated in a Czech government mission to Ukraine, where we visited several medical facilities. The aim was to find out what the situation is in the field of psychiatry and mental health and to identify the necessary assistance that the Czech Republic can offer. From the point of view of psychiatry, my field, it is essential to help Ukraine with the treatment of the effects of trauma on both soldiers and civilians. War traumas often develop into so-called post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This is one of the most severe psychological disorders that tends to affect the rest of a person‘s life. It usually does not go away on its own without treatment and its symptoms tend not to ease over time. In addition, the effects of trauma are also transmitted generationally and negatively affect the lives of the traumatised person‘s descendants.

In Ukraine, I had the opportunity to speak with several psychiatrists and psychotherapists who are treating the effects of trauma. Thanks to the war, Ukrainian colleagues are now extremely experienced in treating the effects of trauma and PTSD, and our field will surely draw on their knowledge for decades to come. It was also interesting to meet the frontline medics who provide transport for the wounded from the trenches. They carry a huge psychological burden, and unfortunately, so do all people exposed to the effects of war.

For me, as an inhabitant of a very peaceful Central European basin, direct contact with the horrors of war was one of the fundamental experiences of my life. The ongoing war is completely outside the scope of what most of us have experienced in the past. The question comes to one with full urgency: What am I supposed to do about it? My initial impulse was to leave everything at home and go directly into the war. This war is so clear in terms of guilt and justice that it gives a straightforward picture of what is right and what is wrong. War seems to simplify life and relativize everything else. This has a somewhat relieving psychological impact, but of course, it also brings major negatives because one can abandon what one has previously striven for many years.

When I became fully aware of this principle, I decided to help simply by doing what I know to do within my professional orientation. I established cooperation with Ukrainian colleagues in introducing innovative PTSD treatment methods. Together with experts from the Clinic for War Veterans in Lisova Polyana, we developed a protocol for innovative treatment of PTSD using structured psychotherapy potentiated with ketamine. This, like other psychedelics, allows a new way of looking at a psychological problem, in this case, the experience of trauma.

Intense psychological trauma, unfortunately, tends to be dissociated from mind control in the psyche, which is the inherent nature of PTSD. Psychedelics overcome this problem and help to place the negative experience within a broader experiential framework. This is one of the reasons they are such a promising form of treatment for PTSD. Our collaboration is now very intense, we visit each other and organise on-site practical training sessions on this treatment approach. On the other hand, we in turn draw on the irreplaceable experience gained by our colleagues from Ukraine in the difficult conditions of war. Introducing psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy is one of several ways to help Ukraine cope with its mental health crisis.

Our help contributes to the hope that our lives have some meaning in this complicated and painful world. And the experience of meaning is one of the main pillars of human resilience in times of adversity, so I welcomed it when Jiri Pasz approached me to support this study. I believe that the nature and scale of the mental health challenges that Ukrainian society faces are in many ways unprecedented and deserve our utmost support. It is the authentic testimonies and voices of Ukrainian colleagues, whose work I value highly, that help us to understand this better and to direct our attention to what matters.

Prof. MUDr. Jiří Horáček, Ph.D., FCMA

Note and Acknowledgement of the Authors

This report aims to introduce readers to the issue of mental health in war-affected Ukraine, which seems to have been sidelined from public, political and media attention. From more than 90 interviews with psychologists, psychiatrists, professionals, and volunteers in the helping professions, as well as those who use their help, we piece together a picture that is essential for orientation and can point to relevant resources for specific assistance. We aim to convey the situation in the words of the Ukrainians themselves in the context of available quantitative data and selected research studies.

The authentic voices are indispensable because available materials and research often focus on only one perspective - either expert studies on specific topics such as PTSD, or quantitative surveys that reduce complex realities to numbers and statistics. During our visits to Ukraine and our efforts to understand mental health in the country, we lacked resources that combined both qualitative and quantitative data. In particular, we lacked materials that provided personal accounts alongside numbers and analytical findings - ones that not only illustrated data but helped us understand the reality of war through individual experiences.

We are aware that the mental health situation in a country as large as Ukraine is very complex, diverse and dynamically evolving. Our findings and conclusions reflect the perspectives of those involved in aid work directly in Ukraine, not among refugees across the border. The interviews were conducted in 2023 and 2024 in the cities of Kyiv, Kharkiv, Kupyansk, Izyum, Dnipro, Odessa, Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk, and Chernivtsi, i.e., in urban centers. In general, the mental health situation is much more critical in the (near-)frontline areas and in regions where there is a lack of psychosocial support. Where no reference to the source is given in the text, this is an interview conducted as part of this research.

We always return from Ukraine enriched. Thank you to everyone who gave us time,

energy, space to share, advice, and often great personal help. Despite the difficult

realities of war, these people are inspiring personal examples for those around them

and for us. From them we can learn determination, resilience, professionalism,

courage, and hope. We feel indebted for their generosity and level of support, and we

want to convey the messages, assessments, and experiences expressed as faithfully

as possible to as wide an audience as possible, in the hope that it will contribute

to a better understanding of the situation and the possibilities for concrete assistance.

We would also like to thank all those who contributed to this report and who

are listed at the end of this report.

Let us think of the psychological wounds and the victims of war, wherever it

takes place.

-

12 333average number of Ukrainians per psychologist (37 000 000/3000)

-

1,2 mil.number of registered war veterans in Ukraine in 2024

-

51,4 %active soldiers and war veterans who expressed a need for psychological assistance

-

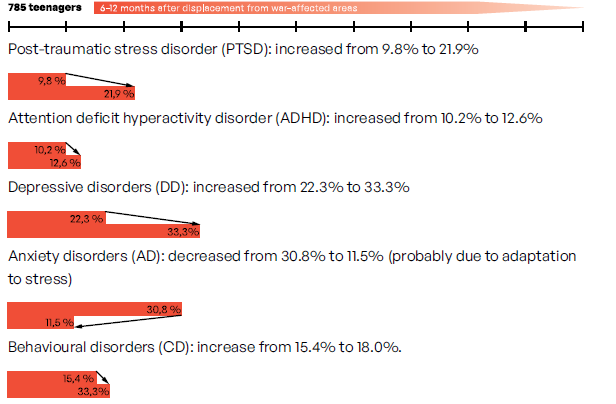

21,9 %adolescents who were displaced as a result of the war and who suffer from PTSD (sample of 785 persons)

-

45 100number of Ukrainian soldiers killed, according to government data

-

50 000estimate of the number of Ukrainians (soldiers and civilians) with amputations

-

3–4 mil.estimate of the number of Ukrainians who will need psychological and psychiatric interventions, including medication and hospitalization

Let‘s not assume we understand it with our own experience

Introduction

„War is the queen of chaos.“

„Intervention at the right time can help and, in the long term, give people their futures back. Psychosocial support programs are some of the least expensive activities in humanitarian responses. But they can have a priceless impact.“

Russia‘s aggression against Ukraine is destroying thousands of lives every day, causing enormous material damage, as well as psychological burden, stress, and trauma with long-term impact. These cannot be quantified or directly mediated. The mental health crisis in Ukraine is therefore, somewhat difficult to grasp and involves staggering but uninformative estimates of how many people may be suffering from mental health problems and illnesses. Even experts do not know how much of this iceberg lies beneath the surface.

The killing in Ukraine will one day, hopefully soon, end, but the psychological scars and suffering will be painful long afterward. The current mental health crisis takes as many forms as many individuals it affects. Experts agree that PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder), for example, only becomes fully apparent in soldiers when they stop fighting, when the immediate danger has passed and everyday or peaceful normality has set in. If people are on the front for months or years, the priority is of course, the fight for survival and, unfortunately, the killing. The struggle for life drastically changes one‘s identity and then one has to find one‘s new self again in peacetime. Similarly, with young children, without developed critical thinking and verbal expression of all the subtleties of mental states, the effects on the psyche cannot now be gauged. They may only become apparent with the passage of years.

It is true, however, that early and effective psychological support or help is the best prevention of serious problems, regardless of age, which can accompany a person throughout his or her life and fundamentally affect the quality of life of his or her loved ones. This report brings authentic testimonies of Ukrainian psychologists, psychiatrists, as well as other professionals and volunteers who work in the field of mental health and at the same time are often exposed to enormous psychological stress and fatigue.

We aim to explain what war causes, how people experience it, and what effective help they try to provide to others and themselves so that they can continue to live, work and overcome what is often the most difficult phase of their lives. In their own words, we aim to show the multifaceted nature of the mental health crisis and positive examples of coping with it. We want to give a concrete human voice to professional concepts and bring to light the experience, projects, and activities of Ukrainian initiatives and professionals that are proving to be helpful but are not receiving enough support.

We should view the inner world of the people of warring Ukraine, whether they have stayed at home or not, with the recognition of the position of an outside observer and listen as much as possible. Although we cannot easily quantify mental health support in measurable indicators of projects and initiatives, it is of vital importance and urgency at this time and in the long term. The future of the people and the country depends on it because only a society that can support the victims of war will be undefeated, in part regardless of the actual outcome. Foreign donors of aid to Ukraine understandably want to see ‚numbers‘ and tangible results of financial support. However, it is also important to support a wide range of activities which, according to Ukrainian experts, are of great benefit to the mental health of society.

In this case, the qualitative and narrative approach plays a crucial role. Professional training of psychologists and psychiatrists, broader awareness of mental illness, creating safe spaces and opportunities to express the emotions experienced, or supporting recovery programmes for the helping professions rebuild irreplaceable human capital. Without it, Ukraine cannot function well in war or peace.

At the same time, promoting mental health in Ukraine strengthens the ability to resist not only the effects of the conflict but also Russia‘s brutal aggression directly. Wars are not only won on the frontlines but also in the minds. If the ability of Ukrainians to resist psychological pressure and psychological warfare is broken, the ability to resist aggression in the long term, whatever its form, will also decline. Without more intensive foreign aid, Ukraine will find it much harder to cope with the crisis, which will ultimately bring risks and costs for its neighbours in Europe.

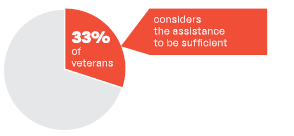

Despite the work of experienced domestic experts and state-sponsored destigmatisation, there is a huge disparity between the urgent needs and capacities in this area, and it may grow further as the war continues. According to an April 2024 IFRC survey, 30% of Ukrainians and Ukrainian women sought some form of psychological assistance after February 2022.2 Further, up to 51.4% of active soldiers and war veterans of the current conflict interviewed in the IOM survey expressed a need for assistance.3 This confirms the progress in destigmatization and the simultaneous massive demand for professional assistance.

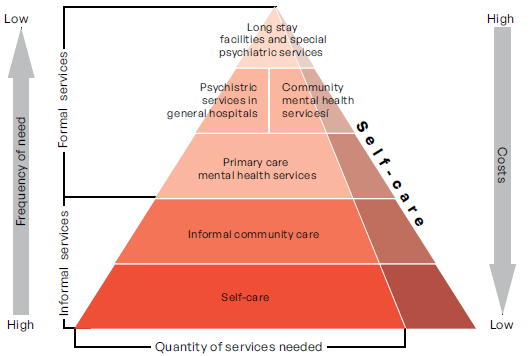

Prevention

Prevention and early help for mental health problems is many times more effective and less costly than dealing with their consequences. Regardless of the human and humanitarian need for assistance, a strong, resilient and defensible society and the subsequent rebuilding of the country is unthinkable without supporting the mental health of individuals. Investing in mental health promotion, including the prevention of illness, also pays economic dividends. „The more we provide trauma education and emotional support, the fewer people will need to go to psychotherapists and psychiatrists,“ says psychologist Katya Taranova.

More support for psychologists and helpers

Psychologists, psychiatrists, therapists, and other members of the helping professions need more support, whether in training, supportive supervision, respite, or even simply expressing our concern and solidarity. It is not enough to invest money in helping. We need to look beyond the beneficiaries of mental health support projects to the specific professionals who provide this help, and not just through indicators of how many consultations they provide to clients.

Safe spaces

Creating safe spaces to express and process one‘s emotions is a prevention for psychological problems. Whether it is young children, adolescents, war veterans, or mental health professionals, absolute safety cannot be created while the war lasts. However, we can help create the conditions and comfortable environment for the brain to temporarily take a break, shut down from feeling stressed and threatened, and for the person to release emotions with professional support.

First Aid

Localisation and coordination

In addition to a greater focus on mental health, foreign aid should be better coordinated and flexible to local conditions. Established Ukrainian institutions and NGOs with experience should play a key role. It is essential that the form and content of assistance responds to the real needs of diverse groups and reflects their cultural, religious, and regional specificities.

Individualisation and diversity

Mainstreaming and Sustainability

Ukraine after the third year of Russian aggression: exhaustion, helplessness, and positive adaptation

“Instead of hoping for an end to the war, we are running a marathon. Or will it be two or three marathons? Who knows...”

The situation in wartime Ukraine is completely outside the categories of our experience to date and to an outsider, it may appear contradictory in terms of positive and negative trends. This is what we experienced during our visits to the country, when optimistic moments alternated with feelings of hopelessness and helplessness. On the one hand, intense psychological exhaustion, extreme stress and emotional strain were evident, which for many in 2024 was compounded by the absence of a horizon of a positive end to the war, the familiar light at the end of the tunnel. The protractedness of the conflict and the drastic losses bring great fatigue and a desire for relief. Compared to the previous two years, Ukraine in the third year of the war experienced a sense of greater distress and loneliness. In the words of volunteers Lili Muntyan and Tetyana Sinyuchina from Kharkiv, “For almost three years we have been fighting, helping and believing in the end of the war. But the contrasting evil that unleashed this war is still with us and is strong. We feel the disappointment of unfulfilled hopes, the feeling of helplessness, anger, and also loneliness.” Psychologist Jelena Kolomoec of Myrne Nebo adds, “Instead of hoping for an end to the war, we are running a marathon, or maybe it will be two or three... who knows?” The discouraging developments on the front, the exasperation at the faltering foreign military aid, and the prospect of its further reduction are causing deepening pessimism, feelings of helplessness, anger, and loneliness among many. From the perspective of the majority of Ukraine’s population, it’s hard to understand the hesitancy to support the country’s self-defence in the face of enemy brutality and a clear perception of right and wrong.

Uncertainty or fear of the future is one of the main stressors, according to mental health experts. In Ukraine, they relate to personal safety, fear for loved ones, financial situations, loss of health and employment, or having to leave home and adapt to a completely new environment or role. In addition to the above, a representative quantitative survey by the International Organization for Migration (IOM), including 4,476 respondents, confirmed the correlation between subjectively perceived mental health and a particular region, with the situation logically being worse in areas close to the frontline.5

The seemingly peaceful impression of a visit to Kiev, Lviv, or other places in Ukraine (unless they are under drone and missile attacks) can falsely lead to the impression that the life of the local people is ‚normal‘ and untouched by the war. However, one only has to visit the local cemeteries to reflect that every Ukrainian may be grieving, missing someone, worrying about someone, or dealing with war-related uprooting, economic hardship, and insecurity. The war is not only being fought on the front, the Russian state is trying to destroy Ukrainians psychologically. „This war is not just a confrontation between two armies. Its goal is to destroy us as an independent nation,“ says war veteran and therapist Vladyslav Haranin. Journalist Zhana Bezpyatchuk also warns of the risk of traumatisation from simply watching media and the need to limit media consumption. “You just need to watch the news about brutality. Sometimes it‘s worse than going directly to the scene as a journalist, talking to witnesses in person and visualizing the scene according to reality.“

While the risks of death or injury vary widely from place to place in the country, Russia is careful to stress that no one is ever completely safe anywhere, ever. „Ukrainians live with the fact that they or their loved ones may die tomorrow. This is a real situation,“ says war veteran Alina Sarnacka. In 2024 alone, Ukrainians experienced over 21,000 air strikes, with the duration being extended to twenty hours. Sleep disruption and, as a result, the overall stress of war manifests itself in insomnia, nightmares, and frequent waking. Sleep is one of the key pillars of mental health. It has a major impact on physical, emotional, and cognitive function, as well as the regeneration of the body and mind. Its long-term disruption will impair the quality of health and life in many ways, including social functioning.

„We are a resilient country, but we will die earlier, not from bombs all the time, but from health complications like heart attacks,“

To claim that in Ukraine most people outside the frontline or shelled areas live ‚normal lives‘ is a fundamental misunderstanding of the psychological and health effects of war and the often permanent stress. The apparent illusion of normal life, that people go to cafes, the theatre, the market or to skate, is often part of an attempt to maintain at least some mental health.

Available academic sources report a rise in the number of suicides and suicide attempts in Ukraine after a major Russian invasion in 2022, although direct official statistics are not available for whatever reasons. According to a report published by the West Ukrainian National University, there has been a significant increase in the first five months of 2024, with 1,522 cases reported in selected regions alone during this period. Research suggests several main factors contributing to the increase, with many people experiencing a combination of these effects:

- Many veterans and civilians suffer from untreated post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which increases the risk of suicidal behavior. Exact statistics are not available, however, R. Tistyk, a member of the Ukrainian parliament, cited the ‘official’ figure as 25,000 in May 2024, while he puts unofficial estimates at around 100,000.6

- Loss of loved ones, health, security and possessions - people who have lost family members or homes are more likely to have depressive episodes and suicidal thoughts.

- Economic instability - high unemployment rates and worsening living conditions increase the psychological burden on the population.

- Lack of psychological support and psychiatric care - even before February 2022, these services were already overstretched and many people were unable to access specialist help.

The Other Side of the Coin

“The transgenerational trauma associated with the Holodomor can be seen in every Ukrainian family. At a party you will have four times more food than you really need, because over-feasting is still a sign of care in our country.”

„It‘s like you‘re constantly facing challenges, but you never have anyone to rely on, to lean on. It‘s probably part of our culture to rely on ourselves, even when help is available. It‘s like you don‘t have that ‚someone can help me‘ formula in your brain. Or maybe you feel like you‘re not at your worst yet to ask for help. You don‘t think you deserve it.“

The Routine of Everyday Life

Many of the professionals interviewed, such as Jana Mischenko, said that they find a source of strength in the positive impact and meaning of their work: 'I get energy from what I do here with the children, it gives me a sense of purpose, that I can bring them a little joy. When a child draws something and feels proud, when they give that picture to their mom and she‘s happy, then she further brags to her mom and she is proud of her grandson or granddaughter. I‘m helping myself by being part of this chain of goodness.“

„I‘ve arranged with a couple of my clients that they can call me anytime. When my phone rings at 2 a.m., I know they‘re shelling Kharkiv again. I often get a call from a young woman who is alone, has no relatives and no support.“

One of the prescriptions for coping with this fragmentation and mental health crisis are the words of Olena Khaustova: „When people can share their problems with someone who is experiencing them in a similar way, or understands them through their own experience, it is an important support. With the help of trained psychologists, we can then work with them.“ She adds optimistically, „It is important that in our country, existing problems cannot be silenced or ignored because people can talk freely about them and seek solutions.“

War as a Catalyst for a Revolution in Care

“Psychiatry in the Soviet Union was closed and, to anyone outside the field, incomprehensible to the point of being feared. Now we are trying to destigmatize the demonic image of the psychiatrist and have had considerable success in doing so.”

Even with foreign support, Ukrainian society has already taken some important steps to improve mental health care:

- The medical faculties have expanded the curriculum for medical students and have introduced elective courses on stress management, trauma work and crisis intervention for various specific groups (children, refugees, people with captivity experience, etc.). There are also internship opportunities for medical students in psychological and psychiatric care;

- The Ministry of Health and foreign donors such as the World Health Organization (WHO) have invested resources and know-how to support the training of general practitioners so that they can better recognize the signs of possible mental illness. They learned about the diagnosis of common mental disorders (e.g. depression, anxiety, PTSD), the use of standardized tools such as questionnaires, and how to communicate with patients about their mental health without stigma. This has increased their ability to correctly and timely refer patients to specialist care;

- Even before February 2022, community mental health support teams have started to operate, particularly targeting harder-to-reach areas close to the frontline, providing specialist psychological and social support;

- Several experienced domestic and international NGOs provide direct support or specific training in trauma intervention and mental health. For example, Doctors Without Borders, Resilience Centres (with support from the Israel Trauma Coalition, among others), and Libereco/Feniks;

- Newly established specialized clinics (Lisova Poljana, Superhumans Lviv) work with clients with psychological problems or with people requiring comprehensive rehabilitation, such as soldiers and war veterans, in a holistic way and with proven and innovative methods;

- Ukrainian experts see the current crisis as an opportunity to build a truly robust and modern system of care and to apply progressive methods of treatment and prevention of mental illness on a mass scale. Despite the lack of resources and persistent stigma in some places, some speak of an „ongoing revolution in mental health care.“7

- At the same time, Ukraine has become, in many ways, an innovative laboratory and, through some activities, a model in the field of care and early prevention, especially for more advanced countries with adequate health infrastructure. Experts and members of parliament with whom we had the opportunity to speak agree on this;

- Ukrainian experts and the government are also working with foreign experts (e.g., Heal Ukraine Trauma) to train, test, and certify professional treatment using psychotropic substances. Ketamine assisted psychotherapy (KAP) is now being introduced for the treatment of PTSD in war veterans. One other example is the legalization of medical cannabis in August 2024 to be used for PTSD relief.

Selected Population Groups

Psychologists,

Psychiatrists,

Therapists

and Helping

Professionals

“As psychologists, we all face the challenge of how to renew our resources, and that our knowledge and education are not sufficient. Most of us did not have professional training in trauma therapy until the war.”

„People need to be reminded now that life can be tasty, no matter what happens. Maybe buy and enjoy something good and replenish your sources of pleasure that way.“

Consequently, these and other helping professionals face enormous amounts of work and psychological pressures from day one, alongside similar stressors and problems as the rest of the population.

Olena Khaustova from Bogolomets University adds,“We don‘t need foreign experts, psychologists, or psychiatrists to teach us how to treat our patients. We have been saying this for a long time. But we need support in clinical trials because they are expensive and we don‘t have the financial capacity for them in particular. This applies, among other things, to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and multiple traumatic brain injury (MTBI), which are very common and difficult disorders. This research may show new avenues for other countries.“

Main Needs

- Creating space for mental hygiene: one effective way to promote mental

well-being and professional growth is through retreats - an organised retreat

in a quiet environment that combines relaxation, mental hygiene and education.

Retreats are an effective tool to manage long-term stress and mobilisation,

reduce the risk of burnout and educate on the latest therapeutic approaches. All

of this supports the long-term sustainability of professionals‘ work and the improvement

of the quality of mental health care in Ukraine. Investing in these programs

is not only a matter of helping individual professionals but also a key step towards

stabilizing and strengthening the entire mental health system. A professional who

is well-equipped for self-care is more effective in helping others learn mental

hygiene.

The retreat program may include workshops and lectures on new therapeutic approaches to trauma treatment, PTSD, crisis intervention, practical relaxation exercises (mindfulness, art therapy, breathing techniques, yoga), groups for sharing experiences and emotions, supervision and building community support among therapists, and techniques for coping with secondary traumatization or emotional fatigue.

- Promote professional supervision: many psychologists work without the possibility of regular supervision sessions to help them cope with the emotional burden of their profession and to get professional consultation when working with clients. Support is therefore needed to increase local capacity to provide high-quality and effective supervision. Supervision provided by international experts, for example, through online platforms, can also help to some extent. Face-to-face or online supervision and peer-to-peer support also appropriately complement the aforementioned retreats and enable therapists to better integrate and maintain the skills they have acquired and to reflect regularly on their mental state. For example, the German organisation Libereco and its Ukrainian program Feniks, which we had the opportunity to get to know personally during the week-long retreat and several interviews, are engaged in this field on a professional level.

- Improve access to therapeutic and training programmes: in many regions, there is a lack of systematic training for professionals, especially in crisis intervention and war trauma work. Programmes focusing on PTSD therapy, crisis psychology, and resilience could increase the effectiveness of assistance. Support for such programmes needs to be implemented through or in close cooperation with local professional institutions. For example, the National Psychological Association of Ukraine,10 medical faculties with departments of psychiatry, or the specialized clinical facilities we list here could be partners for foreign donors.

- Financial and material support: many people in the mental health field in Ukraine work with limited resources or even voluntarily with little or no financial remuneration. Grants, scholarships and financial support could help stabilize their professional situation and provide the necessary equipment, including therapeutic materials and technology. Effective initiatives or projects need support and funding to scale up. Some Ukrainian professionals, for example, do not speak sufficient English, all are overloaded with their work with clients, and cannot institutionalise their projects and initiatives, i.e. to write complex grant applications and manage their administration. The assistance must, therefore, be as administratively unburdensome as possible for both them and the people they help.

- Digital tools and telemedicine: digital platforms for the remote provision of psychological help have proven to be very effective in certain settings, although they cannot fully replace face-to-face meetings. Online therapies and mental health apps can go some way to compensate for the lack of professionals and increase access to care for vulnerable groups.

Children and Adolescents

„I am very worried that our children will inherit this war from us.“

„Childhood cannot be postponed.“

This study of a sample of 785 teenagers tracked changes in their mental health between 6 and 12 months after their displacement from war-affected areas. The results showed an alarming increase in mental illness:

- Girls were more likely to develop depressive disorders, ADHD and PTSD;

- Exposure to additional traumatic events after displacement increased the likelihood of depressive and developmental disorders;

- Children who had previously suffered from PTSD were at higher risk of developing other mental illnesses and had increased sensitivity to stressful events.

Main Needs

- Increase the availability of specialized services for children with PTSD and other mental health disorders, such as trauma-focused therapies (e.g. EMDR, trauma-focused CBT) and training for crisis psychology professionals;

- Promote trauma-informed approaches in education and social services. Schools, in particular, should be prepared to work with children who have been traumatised by war. Teachers and social workers need training and coaching on how to respond to psychological difficulties. Attention to the topic by health institutions, schools and social services is a prerequisite for early detection and a reduction in the incidence of serious disorders. Trauma-sensitive communication skills should be at the centre of support;

- Long-term support for families displaced by war and parents or guardians in adapting to their new environment. Pay attention to the prevention of transgenerational transmission of trauma. Transmission can be mitigated through specific psychological interventions for parents with war trauma, enabling parents to manage their own stress and prevent its transmission to their children. Early recognition of risk signals in children is key - increased anxiety, aggression, sleep disturbance or emotional distance from parents may signal the need for therapeutic intervention. Promoting open communication within the family and helping families appropriately talk about war and trauma without children feeling overwhelmed or emotionally isolated. Intergenerational therapeutic programmes can also help - for example, trauma-focused family processing therapies that encourage mutual empathy and sharing of experiences in a safe environment;

- Promote and better integrate mental health care for Ukrainian children in host countries. Refugee children also need support outside Ukraine. It is advisable to strengthen international cooperation and exchange of experience between Ukrainian and foreign experts on this topic;

- Create safe spaces where children can let their emotions out with professional

support. Moreover, social contact with peers are essential for their cognitive and

psychological development. It is, therefore, important to fund ‚soft activities‘ to

maintain and improve mental health, such as:

- Children‘s stays and camps in peaceful areas, including abroad, offering a real change of scenery, safe place and the opportunity to release emotions under professional supervision. These activities are run by many voluntary organisations such as the Scouts.

- Spaces for play, learning, and communicating with each other in frontline areas or safety risk areas so that children can do ordinary things and really „be children.“

Soldiers and War Veterans

“A soldier described to me how he sleeps with a grenade at home after returning from the front. Imagine the effect on his wife and child? How can they function as partners if she doesn’t understand him at all?”

„The full effects of the war will not be seen for another ten years. Soldiers will return to a completely different life than they know. Many of them will have great difficulty adapting.“

- Cumulative combat stress - After months or years of deployment, some soldiers develop psychological numbness to their survival;

- Moral injury - some soldiers, especially if they have witnessed or been involved in war atrocities, may lose the will to live;

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and combat fatigue - severe fatigue from stressful situations can lead to risky behaviors that look like unconscious or masked suicide;

- Secondary traumatisation and the collective psychological state of the units - in some extreme combat situations, units may share a sense of „invincibility“ or, conversely, „inevitability of death.“

- The length of combat deployment, which is extremely long in the case of the Ukrainian army

- Loss of friends and comrades in arms, sometimes associated with survivor‘s guilt

- Direct exposure to death and brutality, trauma associated with combat

- Lack of psychological support and supervision

- Depression and PTSD

“We left Afghanistan,

but it

stayed in us.”

Main Needs

- Psychological problems are often compounded by injury and require a holistic and comprehensive approach to rehabilitation. Complex PTSD refers to psychological trauma associated with a more severe injury. These include, for example, the so-called kinetic brain contusion due to concussions from a grenade explosion (the so-called signature of war), mentioned above by Xenia Voznitsyna (head of the rehabilitation centre in Lisova Polyana), or severe injuries, amputations, or chronic pain. Only a part of those in need receive the specialized care and rehabilitation provided by the mentioned facilities. Many wounded veterans find themselves without effective support or have to wait a long time for it. Therefore, it is of the utmost importance to expand the services of these specialised facilities.

- Preventing or minimising the risk of trauma must be a priority. Interviewed experts stress the need to intensify the psychological training of recruits before their deployment. Yesterday, today’s frontline soldiers were civilians like us and were not specifically prepared for the stress and trauma of war. Psychologist Jana Ljakovych emphasizes, “It is necessary to prepare recruits for what awaits them in the combat zone. If they undergo psychological training before deployment, the risk of subsequent psychological harm is reduced.” Staff at the Lisova Polyana clinic mention that up to about half of the veterans from heavily decimated units cope with a strong sense of guilt that they, unlike their comrades, survived (so-called survivor guilt).

- Provide ongoing psychological support to activeduty soldiers who are on rotation. This activity is often carried out directly by military chaplains, military and civilian psychologists, and some NGOs. A specialised clinic for veterans in Lisova Polyana, which also works closely with Czech experts, provides three-week convalescent stays to activate the inner strength of soldiers with psychological problems. Capacities are again insufficient and are focused primarily on regaining fitness for military service.

- Support family members, especially female partners, who often bear the burden of physical caregiving and the gendered role of emotional caregiver. They simultaneously experience anxiety and fear for their loved ones at home and on the frontline. Like the soldiers, their families need support as the soldiers are going home on leave or communicating with their families remotely. The widow of war veteran Tetyana Andriyevska (and similarly psychologist Yuri Ihnatenko) would like to see a state-supervised therapeutic programme that veterans with problems would have to undergo before returning home. He adds: “We should not simply let soldiers go to their families during rotations without proper debriefing and psychological support. They often call us during their leave saying they don’t know how to communicate with their loved ones“.

- Promote trauma-sensitive communication and empathy within families,

disseminate information and provide education on how best to adjust as a loved

one to the process of veterans returning to civilian life. This assistance is done, for example, by psychologist Jana

Ljakovych: „Our organization tries

to explain in detail at meetings with

relatives of soldiers what goes on

in the soldier‘s head at the front,

including possible kinetic brain

injury, and how their war experience

can manifest itself when they

return home.“ Multiple psychologists

working with soldiers‘

families confirmed to us that

lived trauma or other wartime experiences similarly divide these families to what

Officer Alexei, quoted above, said about society as a whole. Jelena Kolomoec says,

„Veterans from the front line have an incommunicable experience that civilians do not

understand. They fought for the family in the first place, and now the family does not

‚get‘ them, does not accept their changed behavior. We want to save families. To work

with them and society as a whole to understand what veterans are going through, why

they are in crisis, why they don‘t show emotion like they used to, and why they don‘t

communicate enough. They‘re withdrawn, maybe even aggressive and depressed, or

at the very least experiencing a sense of not being accepted and not being valued".

At the same time, veteran and therapist Vladyslav Haranin, speaking from his own experience, articulates the need for support from the family or neighborhood as follows, “When a soldier returns from war, it is the civilian’s turn to ‘sacrifice’, that is, to give up a piece of his pride, personal space, sometimes even his or her ego, to understand what a war veteran feels. It takes stepping into someone else’s shoes and being a little more forgiving and compassionate towards them to understand that as a result of the mental and psychological trauma, they cannot meet the normal demands and expectations of society, at least for a short period after returning from war.”

- Support programmes of professional reorientation and social integration

of veterans, implemented by veterans’ centres and NGOs. As in other areas

of social care, the Ukrainian state is not used to (and now has limited financial

capacity to) fund the social services of NGOs and charities, as has been the case

in the EU for decades. For example, for the opening and operation of reintegration

centers by non-state social and humanitarian organizations, only UAH 5 million

(EUR 120,000) has been allocated by the Ministry of War Veterans Affairs in the

summer of 2024, with a maximum allocation of UAH 700,000 per grant. Meanwhile,

in an open society with a strong NGO sector, the opportunities to face the “veteran” mental health crisis are greater than in the Russian one, where problems

are more often ignored and covered up by propaganda.

The services of a veterans‘ centre should ideally include this all-around support

and facilities:

- Opportunities for team sports and socialising (with an emphasis on inclusion);

- Training opportunities for professional and personal development (to support those activities and hobbies that veterans individually choose);

- Support for employment and small business development (vocational courses and training). Among veterans, according to a UNDP survey, 37% of those who participated in combat after February 2022 did not have a job;18

- Group and individual peer-to-peer support from veterans who have already been able to successfully resocialise/rehabilitate;

- Support from trained psychologists/psychotherapists and legal assistance for the process of obtaining benefits from the state;

- Psychological support for family members.

- For returning soldiers, restoring family life is crucial, and it is not just about social support and emotional support. Indeed, their motivation to fight is and has been closely linked to the need to protect them rather than to the less tangible notion of a homeland. At the same time, it is the families of soldiers and veterans who may become the first victims of their traumas or may fail to reintegrate into civilian life. Professional psychological support for both parties increases the chances that they will manage the difficult process.

Mosaic of Solutions -

Examples of Projects

and Initiatives

„The war will not end until we deal with its consequences and help heal everyone who can be healed.“

„Therapy works best when it is comprehensive. From classical psychology to some kind of art therapy and physical therapy such as dancing, singing to release emotions in the body. When you only go to classical therapy, there is an analysis of the brain, but you don‘t work with the body.“

War is also a fight for resources - and the vulnerable become even more vulnerable.

Atlant

https://www.atlantsupport.org.ua/en

Resilience Centres

Дім МилосердяDim Myloserdia/House of Mercy

https://www.facebook.com/houseofmercyKiev

Feniks

https://www.libereco.org/en/psycho-social-support-war-crisis/

Gidna

Lisova Polyana

https://www.lisovapoliana.com.ua/

Myrne Nebo Kharkiv

https://www.mn.org.ua/articles/mental-balance-project

Health Clowns

https://www.facebook.com/fayni.nosy.kharkiv

Sane Ukraine

https://www.saneukraine.org/

Scout Movement

https://www.plast.org.ua

Space Clinic

https://spaceclinic.com.ua

Superhumans Lviv

https://superhumans.com/en/

Theater, Dance Projects, Rave

https://playback.org.ua/en/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xoI8EcohISE

https://www.instagram.com/darked_red

Ukrainian Borders

https://rubezhi.org.ua/en/ob-organizatsii

Yellow Sneakers with Julia Borisko

https://www.youtube.com/@ZhovtiKedy

List of interviews

Alina Sarnacka, medical student and war veteran

Alona Udalova, dancer and activist

Anastasija Mul, social worker

Andrej Utenkov, performer and journalist

Anna Sobinova, psychologist

Anna Veličko, psychologist

Artem Harahulja, psychiatrist and doctor

Artem Kaliničenko, NGO worker

Bohdan Ostapčuk, psychologist

Bruno Pedro Pradal, psychologist

Elena Kolomojec, psychologist

Halyna Holub, psychologist

Hana Horodničenko, psychologist

Hatem Marzouk, psychologist

Ihor Šemihon, organization founder

Inna Chartova, psychologist

Iryna Ševčenko, psychologist

Iryna Markevič, psychologist

Iryna Rofe-Beketova, volunteer and scout

Jana Ljakovyc, psychologist

Jana Matvejeva, manager

Jelena Ursaki, social worker

Julija Bačik, social worker

Julija Kulinič, psychologist

Jurij Ihnatenko, psychologist

Jurij Silvestrovič Zynič, Director of the Psychiatric Hospital

Kaťa Taranova, psychologist

Kaťa Kifa, coordinator and founder of an organization

Kaťa Šutalova, psychologist

Kristina Oblučynska, psychologist

Lada Bulach, member of parliament

Lidija Fedorivna, retiree

Lili Muntjan, volunteer

Lilija Rajnivska, dancer

Maksym Djum, mediator and psychologist

Marat Abdulajev, lawyer, founder of an organization

Mariana Mykolajčuk, psychotherapist

Marta Čumalo, psychologist

Marta Syrko, photographer, activist

Maryna Hrudij, project manager

Maryna Rjabič, psychologist

Mykola Syvak, corporate coordinator

Mykyta Žovčenko, patient

Natalija Senycina, organization founder

Nazar Pavlyk, actor and veteran

Oksana Florina, volunteer

Oksana Kuznecova, volunteer

Oksana Mogilko, dance therapist

Oksana Mosyjčuk, hippotherapist

Oleh Melnik, psychiatrist and Director of the Psychiatric Hospital

Oleh Orlov, psychologist

Oleksander Pašenko, psychologist

Oleksandra Jastremska, psychologist

Oleksandra Koroljova, psychologist

Oleksij Pritula, veteran

Olena Chaustova, psychologist and academic

Olena Ivanova, UN worker

Olena Kolomojec, psychologist

Olena Kušnirska, psychiatrist and founder of a children’s clinic

Olha Makarčuk, psychologist

Olha Opalenko, war crimes investigator

Olha Sovjetnikova, project coordinator

Olha Šemihon, social worker

Orest Knodt, volunteer

Orest Suvalo, psychiatrist

Rusana Dyka, psychologist

Slava Strannik, artist

Sofia Runova, artist

Stanislav Ljubymskyj, entrepreneur and founder of a humanitarian organization

Svitlana Kutsenko, head of veteran mental rehabilitation

Svitlana Solopanova, project manager

Svitlana Začynjajeva, psychologist

Svjatoslav, veteran

Tatjana Petrovna, psychiatrist

Teťana Andrijevska, war widow

Teťana Doncova, psychologist

Teťana Hryda, psychiatrist

Teťana Melnyčuk, resilience trainer

Teťana Sirenko, psychologist

Teťana Synjučina, volunteer

Valerija Ljesnikova, journalist and therapist

Velta Parchomenko, psychologist

Vladyslav Haranin, psychologist and veteran

Xenia Voznitsyna, Director of Lisova Polyana Clinic

Žana Bezpjatčuk, journalist

Žana Chmut, UN worker

Authors

Jiří Pasz, MSc.

Journalist, photographer and researcher in the field of health, social and humanitarian aid and development cooperation. He has long specialised in mental health and destigmatisation. He has worked at the National Institute of Mental Health and has field research experience in Ukraine, Uganda, Nepal and Cambodia. He is the founder of the ‚On Your Head‘ film festival focusing on mental health, author of the award-winning book ‚Normal Madness‘ focusing on contemporary psychiatry, and several audio documentaries for CRo on topics such as migraine, ADHD, and addiction.Mgr. Erik Siegl, Ph.D

Publicist, historian by training, and now works as a diplomat. Until 2023 he worked as head of foreign projects at the Centre of Relief and Development of the Diakonia (Czechia), where he coordinated aid in Ukraine. He graduated from the Faculty of Arts at Charles University (Modern History of Eastern Europe and Ethnology) and is the author of the book ‚Defiant Democracy‘ about contemporary Turkey.Prof. MUDr. Jiří Horáček, Ph.D., FCMA

Head of the Clinic of Psychiatry and Medical Psychology at the 3rd Medical Faculty of Charles University and Head of the Centre for Advanced Studies of Brain and Consciousness at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). In 2022, he served as coordinator for mental health during the Czech Presidency of the Council of the European Union (CZ PRES). As a researcher, psychiatrist, and psychotherapist, he has been working with colleagues at the Veterans Mental Health Center in Lisova Polyana near Kiev to introduce psychedelic-assisted therapy in the treatment of PTSD.Methodology

Footnotes

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. (n.d.). A sense of ‘futurelessness’ New data shows severity of mental health challenges for people from Ukraine. Retrieved from https://www.ifrc.org/press-release/sense-futurelessness-new-data-shows-severity-mentalhealth- challenges-people-ukraine.

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. (n.d.). A sense of ‘futurelessness’: New data shows severity of mental health challenges for people from Ukraine. Retrieved from https://www.ifrc.org/press-release/sense-futurelessness-new-data-shows-severity-mentalhealth- challenges-people-ukraine.

- International Organization for Migration (IOM). (2024). The social reintegration of veterans in Ukraine (p. 27). Retrieved from https://ukraine.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1861/files/documents/2024-01/veterans-social_ reintegration_eng.pdf.

- Displacement Tracking Matrix. (2024, November). Mental health in Ukraine: Displacement, vulnerabilities, and support. Retrieved from https://www.dtm.iom.int.

- Displacement Tracking Matrix. (2024, November). Mental health in Ukraine: Displacement, vulnerabilities, and support. Retrieved from https://www.dtm.iom.int.

- Mazepa, S. (2024). Calls against wartime mobilization: Freedom of speech or crime? West Ukrainian National University. Quote of R. Tistyk see, time 4:38, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zQv34pSv8eM

- Quote of Kristina Bohdanova (Sane Ukraine). Scholars.org. (n.d.). New member spotlight: Kristina Bohdanova brings [Online article]. Retrieved from https://scholars.org/features/newmember- spotlight-kristina-bohdanova-brings

- Heal Ukraine. (2023, April). Mental health in Ukraine: Heal Ukraine Trauma Report (p. 4). Retrieved from reliefweb.int.

- Wang, S., Barrett, E., Hicks, M. H. R., & Martsenkovskyi, D. (2024). Associations between mental health symptoms, trauma, quality of life, and coping in adults living in Ukraine: A cross-sectional study a year after the 2022 invasion. Psychiatry Research. https://www. sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S016517812400341X

- European Federation of Psychologists‘ Associations. (n.d.). National Psychological Association of Ukraine. Retrieved from https://www.efpa.eu/national-psychological-association-ukraine

- BBC News. (2025, January 17). Newshour podcast. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.co.uk.

- Médecins Sans Frontieres (MSF). (n.d.). War-torn minds: Navigating mental health issues amid war in Ukraine.Retrieved from https://www.msf.org/war-torn-minds-navigating-mental-health-issues-amidwar- ukraine.

- EPA. 2024. War in Ukraine Is Increasing the Prevalence of Mental Health Conditions in Children, New

Study Finds. https://www.dovemed.com/current-medical-news/

war-ukraine-increasing-prevalence-mental-health-conditions-children-new-study-finds

On study of Prof. Marcenkovsky: European Psychiatric Association Congress. (2024). A longitudinal study of child and adolescent psychopathology in conditions of the war in Ukraine. Retrieved from https://www.europsy.net/app/uploads/2024/04/EPA-2024-War-in-Ukraine-impact-on-mentalhealth- conditions-in-children.pdf.

- Zasiekina, L., et al. (2024). War trauma impacts in Ukrainian combat and civilian populations: Moral injury and associated mental health symptoms. Retrieved from https:// pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37486615/.

- Associated Press (AP). (2024). Deserters and AWOL cases in Ukraine-Russia war. Retrieved from https://apnews.com/article/deserters-awol-ukraine-russia-wardef676562552d42bc5d593363c9e5ea0.

- Early evidence on the mental health of Ukrainian civilian and professional combatants during the Russian invasion https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9724216/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- Pucelik, F. (n.d.). His view on NLP’s beginnings. Retrieved from https://www.nlpacademy.co.uk/articles/view/

frank_pucelik_-_his_view_on_nlps_beginnings/

See also: Globsec Conference. (n.d.). SCARS ON THEIR SOULS: PTSD and Veterans of Ukraine [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VgmmsjYDEso - International Organization for Migration (IOM). (2024). The social reintegration of veterans in Ukraine (p. 27). International Organization for Migration. Retrieved from https://ukraine.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1861/files/ documents/2024-01/veterans-social_reintegration_eng.pdf

- Conference „Inovativní postupy v oblasti duševního zdraví a udržitelnost systémů zdravotní péče“. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zQv34pSv8eM (час 4:38).

- The MHPSS Network. (2022, December 5). Ukrainian Prioritized Multisectoral Mental Health and Psychosocial Support Actions During and After the War: Operational Roadmap. Open Document.

Acknowledgements

The editing and translation of the interviews was done by Svitlana Shevchenko, Tereza Košnářová, Lucie Hrabtsova, Valeria Lesnikova, Olga Likhachevskaya, Veronika Andrashko, Anastasia Boldyreva, Elvira Hluchanich, Katya Gazukina.

Valuable feedback was provided by Vojtěch Hönig, Katka Krejčová, David Frýdek, Tereza Košnářová, Pablo lo Moro, Sabina Malcová, Zbyněk Wojkowski, Jelena Kolomojec, and Karolína Sieglová.

The text was reviewed by Prof. Jiří Horáček.We would like to thank all crowdfunding contributors at donio.cz for their financial contributions (we would not have managed this without you!).

NGO Libereco also contributed financially to the conduct of interviews. Though it is not affiliated anyhow with the content and writing of this report, Imke Hamsen and her team were helpful with their open approach and sharing of experience.

Our great thanks also go to the NGO Myrne Nebo (Stanislav Ljubymsky, Oleksander Varivoda, Dmytro Lunin, Jelena Solapanova).

Responsibility for the content of the report and any errors or inaccuracies lies solely with the authors.

Impresum

Report Title:

Invisible Wounds, The mental health crisis in Ukraine through the eyes of local

experts (April 2025)

Authors:

Jiří Pasz, Erik Siegl, Jiří Horáček

Photos:

Jiří Pasz

Graphics:

Michal Puhač

Proofreading:

Georgette Townsley

Contact:

Jiří Pasz |+420 777 236 153 |Erik Siegl |+420 731 593 210 |

Copyright and licensing terms:: This document is licensed under a Creative Commons license: CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 (Non-profit use, no modifications). You may freely share the material, provided you credit the authors, do not use it for commercial purposes, and do not modify it.

Funding and support: This report was produced as a private initiative of the authors. The research in Ukraine was supported by a crowdfunding fundraising campaign and a contribution to the conduct of interviews in Ukraine from NGO Libereco. The work of Professor Jiří Horáček was supported by the Foundation for Psychedelics Research (PSYRES), which supports the implementation of innovative methods of PTSD treatment in Lisova Polyana. n-ost, a network for border crossing journalism in the Eastern Europe, financially supported the translations from/into Ukrainian and English.